By Walter Witkowski

As published in the Lincoln Eagle

George H. Sharpe 1828-1900

|

George H. Sharpe – One of Kingston’s Buried Treasures

There was something on the TV or

radio the other day about how there are no heroes, just average people who rise to meet extraordinary situations.

That certainly has the ring of truth to it. There was a Kingstonian, back in the 1800’s who, although he may not have been just

“average” certainly grew to meet the extraordinary circumstances that gripped the country during the Civil War. His name is George Henry Sharpe.

I had the distinct honor of presenting a talk about General Sharpe to the nascent organization, “Kingston’s Buried Treasures” on

September 21st last. These folks organized the remembrance of Governor George Clinton held recently in uptown Kingston and are

now looking to educate the community on Kingstonians whose impact on the country and perhaps the world has been long overlooked or forgotten.

The presentation on November 16th at 5:30 will be County Historian Anne Gordon speaking about Sojourner Truth. For further

info about KBT, call 845-340-3050 or email to poneill@courts.state.ny.us. The talk for December will be presented by Stuart Murray and will

be about Thomas Cornell. The date is December 14th. The time is 5:30. All talks take place at the Senate House Museum.

I figured it would be a shame to let all the research on General Sharpe go to waste so here’s my way of sharing.

George was born on February 26, 1828 in Kingston, NY to Henry and Helen Sharpe.

Described in his youth as wiry, blond-haired and in love with books, study and learning,

George attended Kingston Academy and Albany Academy. He then attended Rutgers University,

starting at the age of 15 and graduating with honors in 1847. He gave the Salutary Address

in fluent Latin (!!) and then attended Yale University Law School and graduated in 1849 at

age 21. After traveling abroad for three years, part of the time serving as an attaché in

the US Embassy in Vienna, he returned home. He was described in his early manhood as not

handsome but had much charm and personality. He was on the short side, his blonde hair was

now brown, his build was medium and he was known as a good horseman.

After he passed the Bar, George became a successful attorney, investor and a member of the

20th New York State Militia, being elected captain of Co. B in August of 1858. Although he

resigned his commission on April 5, 1861 because of business obligations, he withdrew the

resignation after hearing Ft Sumter had been fired upon. George hurried back to Kingston and

began recruiting to bring his Co. E up to full strength. He and fellow 20th Militia captain,

John Rudolph Tappen, set up shop at the old armory, what is now St. Joseph’s Church in uptown

Kingston. In one day, they signed up 248 men.

Sharpe and Tappen then were assigned the duty of drilling all of the 20th’s new recruits. When

the 20th left Kingston for New York City aboard the steamer Manhattan, Sharpe described the

voyage: “Our whole trip was an ovation.” Thus the Hudson River Valley expressed its appreciation

to the first non-New York City regiment to depart for the seat of war.

Now, the 20th basically did guard duty to ensure the railroad stayed open as it ran through

Maryland, specifically Baltimore. Recall that Maryland almost seceded, which action would have

solated Washington, DC from the rest of the North. This therefore was an important mission.

Captain Sharpe performed his duties well, except for one lapse of good judgment. See Seward

Osborne’s book, The Three-Month Service of the 20th New York State Militia April 28-August 2, 1861

for the details. Sharpe, by all accounts, performed well for the rest of the 20th’s term of

service. When the regiment returned to Kingston in July, Sharpe returned to his business affairs.

However, when Lincoln called for 300,000 more volunteers in the summer of 1862, Sharpe, after

being asked by NY Governor Edwin Morgan to raise a regiment, left a sickbed and recruited over

1000 men from Ulster and Greene Counties in a record 22 days.

With virtually no training, the new regiment left for the warfront on August 22, 1862, to serve

three years or the duration. It was George Sharpe who chose the number for the regiment: the

120th New York. Sharpe said he chose the number “in order that in name as well as in feeling,

we might be associated with the old 20th.” The regiment trained at Fairfax Court House, VA.

There, not only the men, but also now-Colonel Sharpe learned the soldier’s trade. Sharpe found

he had to deal with such mundane command responsibilities as hygiene, drunkenness, thievery among

the men and even deserters and insubordination.

The 120th joined the Army of the Potomac (AOP) in time for the Battle of Fredericksburg. Luckily,

the 120th was in a reserve role during the battle and suffered only several wounded. (The AOP,

under the leadership of Gen. Ambrose Burnside, lost some 12,600 men at Fredericksburg). Col.

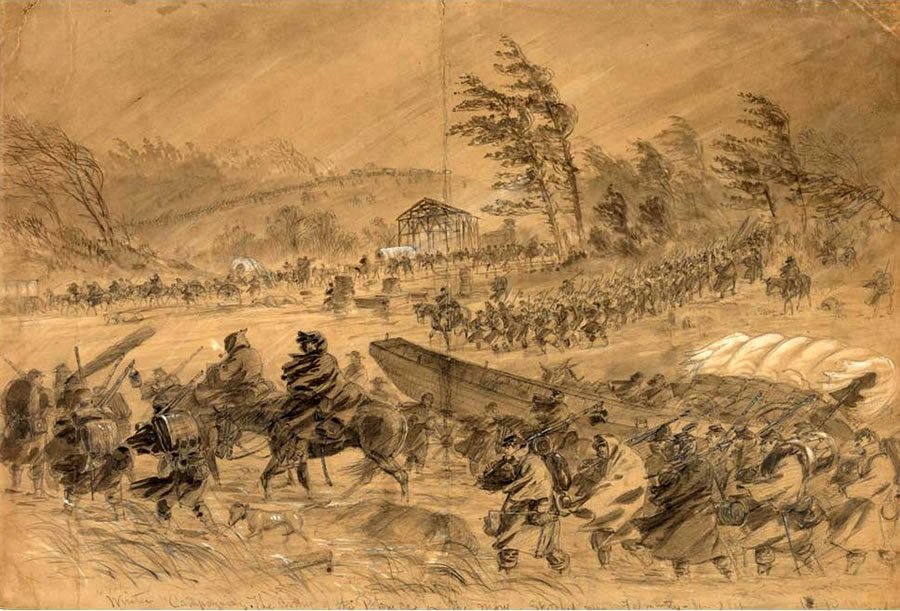

Sharpe also led the 120th on the infamous “Mud March” of January 1863, Burnside’s winter campaign

designed to flank General R.E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia (ANV), and retrieve Burnside’s

reputation. As God would have it, the Heavens opened and the rains so mired the roads that men,

horses, wagons and artillery all had to return to camp after floundering for 2 days. Sharpe

said after the march, “I think we are stationary now. Nothing but balloons can move us.”

"Mud March" January 1863 Col Sharpe’s regiment had been reduced in number from the 900 who left Kingston in August to

a bit over 400 officers and men fit for duty as the Mud March got underway. Sharpe, ever

solicitous of the welfare of the troops under his command, tried to have the 120th assigned

to the army’s Provost Guard, which the 20th Militia was a part of. The effort failed but it

got Sharpe noticed by General Marsena Patrick, the AOP’s Provost Marshal.

And that’s when our “average” Kingstonian’s star within the AOP started to rise.

“Fightin’ Joe” Hooker took over the AOP after Burnside got sacked in February 1863. Hooker wanted

to beef up his “secret service”, that is, that part of his army directed to provide the army

commander with information about his enemy, Robert E. Lee and his ANV. Up till now, intelligence

about the ANV had been woefully inadequate. General Hooker approached Patrick to set up an

organization to do the job. Long story short, George Sharpe got the nod.

Sharpe brought his native intelligence, attorney’s analytical thinking, strong work ethic and

organizational skills to the task. Over the next few months, Sharpe and two early assistants,

fellow Kingstonian Captain John McEntee and John Babcock, a current member of the “secret service”, established

the Bureau of Military Information (BMI). With never more than 70 full time people

on the payroll, Sharpe built an organization that is now recognized as “the first all-source

intelligence” organization in US history. The BMI did not just gather intel and pass it up the

chain of command. No, they “obtained, collated, analyzed and provided reports” based on multiple

data sources, like cavalry scouting, spies, signal flag and telegraph intercepts, info from

Confederate deserters and POWs, etc.

The Official Records of the Civil War are replete with reports from Sharpe, McEntee and Babcock,

as well as other BMI actors, to the various commanders of the AOP from February, 1863 until

Appomattox. In the National Archives, there are boxes and boxes of reports written in Sharpe’s

own hand that further testify to the work done to enable the AOP to successfully confront and

defeat Robert E. Lee.

So, Sharpe’s good intel gave Hooker a very clear idea of Lee’s Order of Battle (units in his

army’s corps, divisions, brigades and regiments), where the enemy units were, etc. and what they

might be up to. Hooker used this intel to help him plan the Chancellorsville campaign. As we

know, the campaign failed because Hooker lost his nerve and not through any fault of the BMI.

The AOP lost around 18,000 in dead, wounded and missing.

After the battle, attempts were made to secure a flag of truth so wounded prisoner exchanges

could take place. The Confederates refused. Hooker asked Col. Sharpe to try and secure some

sort of exchange. Sharpe agreed, then crossed the Rappahannock and met with a Confederate officer.

When asked about an exchange, naturally the Reb officer said he had no authority to make such

an arrangement. Well, Sharpe played another card. He asked if the officer was hungry and could

he use a good meal. Naturally that officer was up for a good meal. Sharpe brought over some fine

food and spirits and wined and dined him. Well, the officer, after a second bottle of champagne,

agreed to a release of wounded Union soldiers. Some 4,000 of them. Sharpe stated he considered

this as one of his finest achievements during the war.

The war went on. Sharpe’s BMI kept collecting intel. When General Lee decided to built on his

spectacular Chancellorsville victory by invading the North for a second time, it was Sharpe’s

BMI that got wind of the ANV’s movement. A recent scholarly study now concludes that it was the

data provided by Sharpe that got Hooker to realize Lee was moving North. Sharpe’s report to

Hooker stated all his sources concluded the ANV was “under marching orders” for a campaign of

“long marches and hard fighting….All the deserters say the idea is very prevalent in the ranks

that they are about to move forward upon or above our (the AOP’s) right flank.” Hooker reviewed

Sharpe’s intelligence and put the AOP in motion to follow Lee north. This action protected

Washington, DC and enabled Union troops to be in Gettysburg on July 1, 1863 in time to hold the

high ground! That’s our soldier from Kingston at work!

One other Gettysburg story. On July 2nd, after a second day of desperate fighting, General Meade,

who Lincoln named as the new commander of the AOP while the army was marching toward Gettysburg,

held a counsel of war at his HQ to decide whether or not to stay put and fight Lee another day.

Colonel Sharpe was called into the meeting and asked what his intelligence gathering indicated.

Sharpe asked for an hour of two’s grace to consult with his team. He returned 2 hours later and

told the assembled generals that the only troops Lee had not yet engaged in the fight was Pickett’s

division. General Winfield Scott Hancock sat up and said to Meade, “General, we got them nicked!”

The decision was made to stay. Pickett (and others) charged on July 3rd. And failed. Here again,

Sharpe was an actor in one of the most momentous decisions in the Civil War.

Now the story goes that a plate of hard crackers and a bottle of whiskey were in the Leister House

room where the war council was held. The story goes that Sharpe and others looked longingly at

those victuals but no one partook. Well, after proclaiming that Lee was “nicked”, and deciding to

stay and fight it out, it’s said that Hancock then looked at that plate and at Sharpe and said to

Meade, “General, don’t you think Sharpe has earned a cracker and a drink?” Apparently however, no

one partook because it was felt there was not enough to go around. Comrades!

Leister House Well, again the war went on. Sharpe and the BMI continued to produce accurate intelligence on the

ANV and on the state of Confederate morale at home as well. General Grant, upon being ordered East

by Lincoln to take command of all Union armies, made his HQ with the AOP. He soon learned about

Sharpe and came to appreciate the job he was doing. So much so that Sharpe was promoted Brevet

Brigadier General in December 1864, and Brevet Major General by the war’s end.

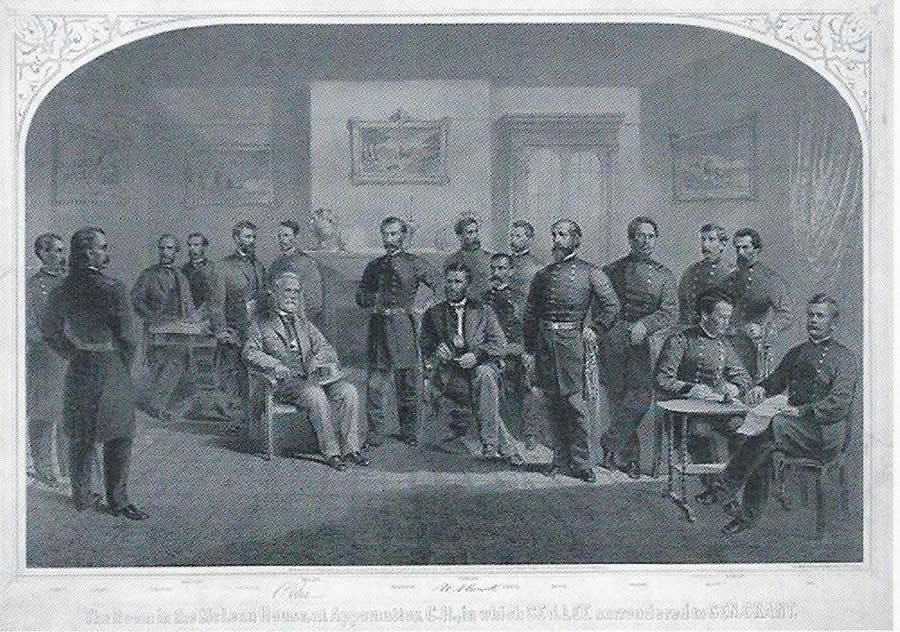

There’s one more time (at least) when Sharpe found himself a part of a fateful moment in the Civil

War. It was at Appomattox when Robert E Lee surrendered to U.S. Grant. Sharpe was designated by

Grant to parole the ANV. Basically, that meant that the Confederate POWs gave their word not to

take up arms against the US until formally exchanged. Of course, they were just going home, as

their war was over.

McLean House - Surrender of Robert E. Lee Anyway, General Lee approached Sharpe, via a staff member, to have a parole issued to him and his

staff. Sharpe was at first reluctant, thinking it would be presumptuous and disrespectful of him.

Lee insisted and, after consulting with General Grant, Sharpe issued the parole. Sharpe, upon

consideration, added the following:

“The within named officers will not be disturbed by the United States authorities as long as they

observe their parole and the laws in force where they reside.”

And Sharpe himself, as Assistant Provost Marshall of the AOP signed the document.

Okay, you say. Just a bit of bureaucratic nonsense. Well, as it turned out, the document was

instrumental when the Radical republicans in Congress were contemplating bringing charges of

Treason against Lee. Lee was able to produce his parole, show he had been properly paroled,

demonstrate that he had observed the terms of the parole and therefore should “not be disturbed

by the US authorities”. When General Grant heard about the proceedings, he addressed the committee

and insisted the matter be dropped as indeed Lee was properly paroled, and that he, Grant, would

resign his Lieutenant Generalship if this was not done. Congress being Congress, knowing hoW

popular Grant was with the country, dropped the matter.

Thus, Sharpe, our Kingstonian, was instrumental in keeping R.E. Lee from a potential date with the

gallows. This is no small thing.

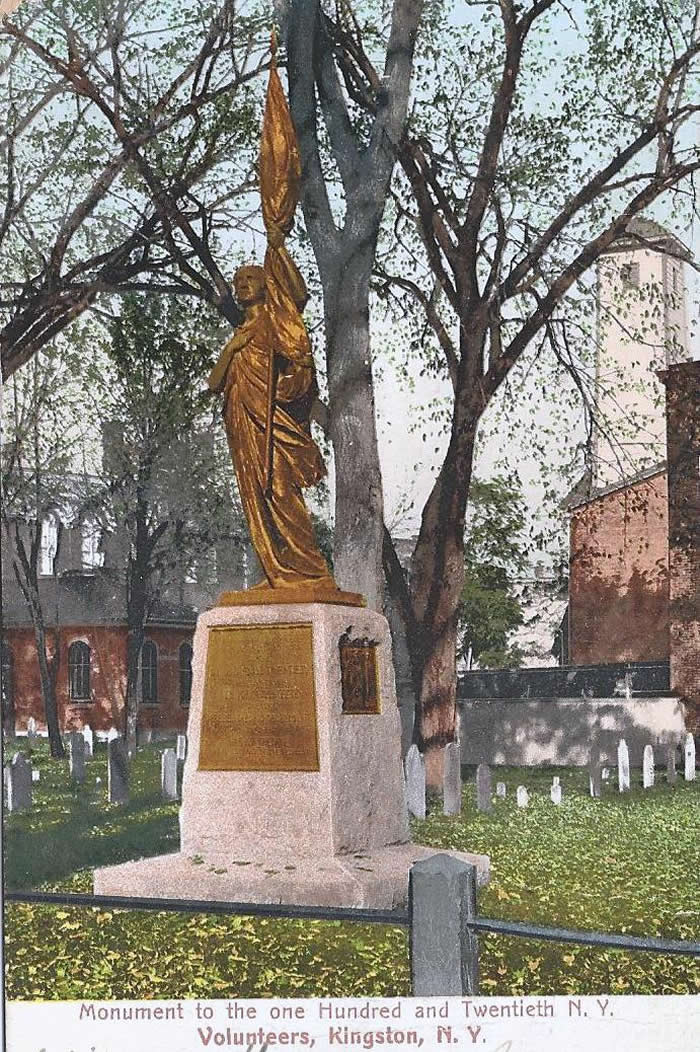

Well, Sharpe had a full post-war career and was very active in veterans affairs after the war.

He maintained deep affection for the men of his 120th NY. Indeed Sharpe is the only known

regimental commander to fund and have erected a monument honoring the fighting the men of his

regiment. You see that monument still today in the Old Dutch Church graveyard at the corner

of Fair and Main.

Monument to the 120th Regiment George Henry Sharpe is buried in the Wiltwyck Rural Cemetery near his comrade John Rudolf Tappen, and others. Stop by and visit. It’s a wonderfully quiet spot for a heroic man to rest. |

THIS IS THE FINE PRINT