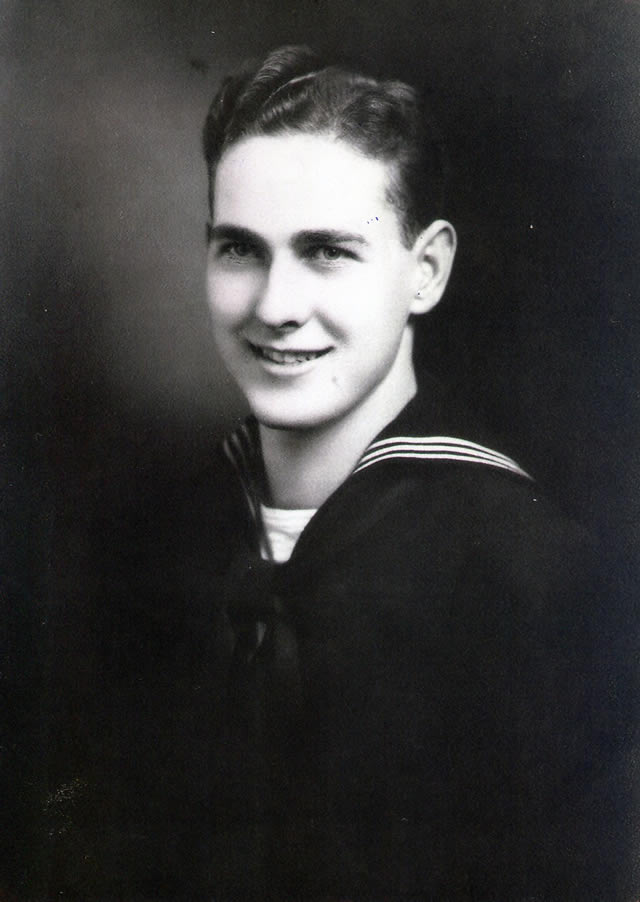

CHARLES E. WERNER 1943

Charles Werner passed away on October 14, 2016 at the age of 94 years, 8 months.

He will be missed by many people.

My uncle, Charles Werner was on the original crew of

the CK Bronson and served on her from her commission in June 1943 through the end of the war in 1945. (There can only be one "original" crew and those sailors were forever referred

to as "plank owners" of their ship.) In 1998 he reminisced about his experiences to family and the following memoir was prepared by his

daughter-in-law, Susan who did a wonderful job of editing and transcribing his experiences. Reprinted here with his permission - All Rights Reserved by Charles E. Werner.

The CK Bronson, DD668, was a Fletcher class destroyer that was designed for a peace time crew of 250. During war time the ship carried a crew of about 340 persons.

CHARLES E. WERNER

ENLISTED UNITED STATES NAVY - 25 SEPTEMBER, 1942

NOTICE OF SEPARATION FROM U.S. NAVAL SERVICE IS RECORDED IN BOOK 9, PAGE 448 ULSTER COUNTY CLERK'S OFFICE

SERVED ON DESTROYER CLARENCE KING BRONSON - DD668 2100 TON, FLETCHER CLASS DD, COMMISSIONED JUNE 11, 1943, BROOKLYN NAVY YARD

ELIGIBLE TO WEAR THE FOLLOWING MEDALS:

After a month of boot camp at Green Bay, Illinois (Great Lakes Training Camp), I went to Detroit,

Michigan to attend four months of Electrical School, then to Pier 92 in New York City. The Queen Mary docked at the next pier one afternoon. She had German prisoners of war on board.

That evening, some managed to escape. Many were captured hanging on to pier pilings by Coast Guard Cutters. Some tried swimming the river, others were found in parked cars. I remember

seeing dripping wet Germans squatting all around the lobby of Pier 92, a sailor behind each, with a gun.

Lido Beach, Long Island was my next destination. This turned out to be a staging area for destroyer crews. At this time, my ship (the Bronson) was still in a New Jersey shipyard. Approximately

a month later, my ship was commissioned at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

After a shakedown cruise to Bermuda, we escorted a cruiser on her shakedown to Trinidad, then up the coast through the Cape Cod Canal, to Portland, Maine. Here, we picked up a destroyer

tender and escorted it to Hawaii, by way of the Panama Canal and San Francisco. At Pearl Harbor, Hawaii we escorted a minelayer to Tarawa, Gilbert Islands near the end of the invasion.

There, we joined the 3rd Fleet, which in a short while returned to Pearl Harbor.

Our destroyer was now designated a squadron leader. On board was the Commodore and his staff of officers who commanded the screen of ships (destroyers and cruisers) surrounding the major

ships (Carriers and Battle Wagons), as a line of defense for the major ships.

My first impression of a destroyer was, "How can I live in such cramped quarters?" As time went on, these "Tin Cans", as destroyers were called, became more and more spacious. I was

assigned to the top bunk, which were three high in the forward bunkroom in the bow. My battle station became the emergency diesel room throughout the entire trip. The emergency diesel

drove the generator to provide electrical power to any part of the ship in case of a casualty. Life on board was routine, with four hours on, eight hours off. The four on was spent in

the forward or aft engine room on the electrical boards. During off time in daylight hours, you were expected to do any maintenance that was necessary.

After leaving Pearl Harbor, the ship was in enemy territory constantly. Shore leave was out of the question since there was no place to go. When a few island groups were successfully

invaded, we were allowed to stretch our legs on deserted islands, a couple of times. Not the entire crew at once, of course. The ship supplied us with a couple of beers, a sandwich, and

said, "Enjoy". Both of the times I went, things happened.

On one beer party, the whaleboat came to pick us up and was beached by a wave. The Boatswain had us push as he gunned the motor. The prop created a powerful suction, which sucked a

sailor into its blades, killing him. Not a happy trip!

On the next outing John Homan, my friend, suggested that rather than party, we should visit with the SeaBees on a near island. This required quite a swim, but we figured it would be O.K.

It would have been, however, a riptide or strong current was preventing us from making any progress to the island, and in fact was carrying us away from our island. It was now sweeping

us out into the lagoon. The current carried us past numerous ships, but we could not make it to any of them. Hours later, we sighted a ship we hoped to intercept. When we were about

to be swept past this one too, someone noticed us, and a whaleboat came to pick us up. It was our last chance for rescue since the next group of ships was way off in the distance. Up

the ladder of the Destroyer Tender in nothing but our shorts, the Quartermaster couldn't believe we could have swum that far. He wanted to return us to our ship. We had other ideas since

our clothes and wallets were on the island. When their whaleboat approached the beach we had to dive in and swim. I barely made it to the shore, my arms were like dead weights. The party

had started mid-morning, and now it was almost dark. Luck was with us again. By now the crew should have returned to the ship. Most were, but the Commodore needed the whaleboats. We found

six to eight men still waiting. We built a fire and it wasn't until about two in the morning when out of the darkness someone shouted for us to swim. I did but that was the last swim I had

for years. It felt good to be on board ship again.

Let me tell you about storms. In the pacific they are called Typhoon's, which are similar to hurricanes here, with rain and big winds. When a Destroyer hits a wave it buries itself

completely in it. The ship is then lifted up with the crest of the wave, and comes out with only its props in the water. Then it drops headlong into the trough and

smacks into the next wave. This battering forces you to hold on all the time, even while sleeping. I used two belts buckled together, slung under my bunk over my middle and buckled again.

This prevented my being thrown out on my ear. Waves broke many arms and banged many heads. When the ship comes out of the crest it fish tails violently throwing you from side to side. By

the time a storm ends all your bones ache.

No lights were ever allowed topside at night. Our hatches were wired like refrigerator doors. Imagine getting forward to aft on the main deck, at night, in heavy seas. Very dangerous

if you did not judge the wave correctly. If it were not for a rope net fence along the ship's edge, many would have been washed overboard. No one ever went forward of the weather deck,

especially during storms. The bow is most generally under water.

On one occasion, after over a month at sea, we entered Ulithi Lagoon (I believe) as a Typhoon hit. Low on fuel, we made four attempts to approach an anchored tanker. On the fourth

attempt we rammed the tanker. It was time to give up. We pushed in our bow and looked like a Bulldog for the rest of the war.

Orders were given to ride the storm out at sea. We used our engines just enough to keep our bow into the wind. We felt all alone, only occasionally sighting a ship. Sadly, three

of our squadron, the Spence, Hull, and the Monahan, ran out of fuel. Now at the mercy of the sea, they capsized and sank. Seven hundred and ninety men perished. Later, stateside, the

Captain of the Hull (who had been rescued from the sea) replaced our Captain. The category-four typhoon of December 1944 was later referred to as Halsey's Typhoon.

(ed. note -UPDATES ARE FROM AN INTERVIEW JANUARY 30, 2016) After the invasion of the Philippines, we entered the South China Sea, to French Indochina, Hong Kong, and Saigon, looking for remnants of the Jap fleet. We encountered especially

rough seas during this time. Two days before exiting the Strait of Formosa, we were hit by a huge tidal wave (I called it a "tidal wave" but we were told it was a "Rogue wave- the sky was

clear and blue and there was no storm in sight).

I had just finished a four to eight p.m. watch in the after engine room.

The engine rooms are dreadfully hot, especially since we were in the tropics. I went up on the super structure behind the number two stack to cool off. A spare parts box is welded to

the deck here, and we always used it as a seat. Lucky for me, I saw this wave coming. It looked like a mountain dropping on me. Also behind the stack is a tube running to it's top (of the funnel stack).

It is used like a periscope by the fire room to observe if smoke is being made, which is a no-no. I wrapped my arms around this pipe. When the wave hit, I had all I could do to hold on.

I thought I would drown before we righted ourselves. (my legs were out straight behind me and I thought I was going to be ripped from the pipe as whe water rushed over me. I was

completely submerged for a VERY long time). The ship had nearly capsized when it rolled to dangerous angle. I then heard a cry for help. I tried to move in that direction but

found a whaleboat smashed to bits around number two stack. (The wave must not have hit full broadside but must have washed generally from bow to stern. The whaleboat had come loose from way up in

the bow of the ship. It had been smashed to bits and was just dumped over the side. ) The quad forties forward and torpedoes aft saved my skin. I moved forward along the other side

of the super structure and came

out over the deck winch on the main deck. The injured man lay by the deck winch. Help had already arrived. (Uncle Charlie says he remembers the ship's doctor, Dr. Robert

J McManus, as "everyone on the ship had to see the ship's doctor one time or another". (JWW- I received the following note from the son of Dr. McManus.)--- My dad was the Medical Officer on board and a plank

holder, Dr. Robert J McManus. He came aboard as a Lt JG and left in early 1945 (when the ship sailed to SF from her first tour) as a Lt. Cmdr. He never talked much about his personal experiences

on board but from the Navy Records - fitness reports, medal commendation (Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Cluster) etc. I’ve managed to put together much of his history. His medal was earned for

taking care of a sailor who got disemboweled on deck during the typhoon – Dad operated on him on the ward room table. I actually have an email from the pharmacists mate who assisted him recalling

the incident. Very emotional.) As the wave hit, he had grabbed the deck winch to prevent being washed overboard. The impact of the wave had torn the metal bulwark loose from the weather deck. As it passed, it ripped

his stomach open. At the same time, a deck hand was dumping garbage from the galley, which is near the deck winch. He was later found in the bloomer of number three, five-inch gun mount.

This mount is at least fifty feet aft and probably twenty to twenty five feet above the main deck. Next day, we buried him at sea. For a burial at sea, a five-inch shell is tied between

your legs as ballast, then they sew you up in a canvas sack. As shots are fired and a bugler plays taps, they slide you overboard. The other injured crewman was transferred to a major ship

sick bay.

That night we went through the Strait of Formosa. Next morning while fueling from a Battle Wagon, a Carrier took a Jap bomb through its flight deck. A couple of our fighter planes pursued

the bomber and zapped it out of the air. Back on the Carrier, a fire broke out in the hangar deck. To help rid the deck of water and oil, a list was put on the ship. Fighting the fire, a

crewman lost his grip on the hose and slid out of the open hangar door, into the ocean. We moved in to assist in his rescue. Stopped dead in the water while picking up this man, we had all

guns blazing at a kamikaze heading for the Carrier. This Jap led a charmed life, until he hit the Carrier Bridge, wiping out the entire bridge. Formosa sent huge flights of planes over us

the rest of that day. My GQ (General Quarters) station was below deck, so what I am describing on these pages is only a small percentage of what really happened.

At a lull in another air attack, we were being fed in the chow hall. On long GQ's., sandwiches and coffee were usually brought around to battle stations. I came out on deck to see a Betty

Bomber (a twin engine bomber) approaching our fantail at wave level. It passed so close, I could see the pilot's faces. We were small peanuts and they wanted a major ship inside the perimeter.

I watched as the plane headed for a Carrier. The plane had to gain altitude to drop its bomb and we began firing and made a hit. The plane passed harmlessly over the flight deck and crashed

in the ocean.

Since I've started telling war stories, here are a few more .................................

One afternoon at Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands our ship fueled at a tanker, the Mississinewa, then anchored close by. Before dawn next morning, GQ sounded after a huge boom, which shook

the ship. When I arrived, topside, the tanker was nothing but a blazing, smoking area on the water. Gone! An enemy sub had released one-man suicide subs (Kaitens) which entered the

lagoon undetected. Destroyer depth charges took care of all the midget subs.

During the first battle of the Philippine Sea, we were under air attack most of the day. Then our Carriers released their planes to pursue the enemy task force. Returning late that night,

our planes, low on fuel and some with battle damage, could not make it to the decks of their Carriers. All ship's lights were ordered on and pilots to crash land near a destroyer. I manned

one of our three-foot searchlights, trying to locate the pilots, the waves making it difficult. I remember one pilot every time he came up on the crest of a wave, blowing his whistle with all

the breath he could muster. Our rescue technique was to drape a cargo net along the side of the ship. One or more men would wear harnesses with long ropes attached and go overboard to swim

to the pilot and help him up the cargo net ladder. We picked up quite a number that night.

The second battle of the Philippine Sea was a bit different. It started with the usual task force to task force air attacks, which lasted from before sun up till late afternoon. At this time,

we were ordered to prepare for surface engagement. Four Cruisers and my squadron of Destroyers gave chase to the Jap fleet. Some of their ships had received air damage. The first target was a

huge Jap Carrier. No enemy aircraft were visible. Our Cruisers softened the Carrier with their eight inch guns. Our approach was in Indian fashion, while the Cruisers zigzagged firing when

they came broadside. My Destroyer was told to make a torpedo run. As we made the approach to release our torpedo, the Carrier began to explode internally. We stood by as she up-ended and sank.

I still remember all those poor Jap sailors looking up at me from the water. Not a survivor was picked up this night. Next, we located a Jap Cruiser. After a little softening up, a couple of

our Destroyers sunk it with torpedoes. Later that night, three Destroyers were chased down and sunk.

The invasion of Iwo Jima was something else. This island was really fortified, its caves and tunnels proved hard to bomb. On D-Day, the Bronson lay just off the beach bombarding. The Marines

in landing craft passed us on the way to the beach. After the initial landing, we made runs under Mt. Suribachi. The gun mounts located in caves returned our fire on each pass. As night approached,

we took a position near the beach and fired star shells all night at intervals to supply light for the Marines ashore. I remember a message over the loudspeaker stating that the American flag had

been raised on Mt. Suribachi.

My task force made the first and several other raids on Japan proper as fighter escorts for long range B-29's. After leaving Iwo Jima we headed to Japan on one of these raids. We were assigned

picket duty, meaning we would travel twenty five to one hundred miles ahead of the task force to sweep and destroy any enemy shipping, fishing San Pans included. One night we had a running battle

with a squadron of Jap Destroyers; never did I see so many tracers coming at me at one time. Luckily they were bum shots. What the outcome of the battle was I do not remember.

Back to life aboard ship. I mentioned before how hot engine rooms were. Well the tropics made the whole ship a hot box. In fair weather the crew would sleep under the gun mount, searchlights and

super structure. Sweat would make your clothes stiff as a board. I usually went though three sets of clothes a day. Laundry was no problem. The ship did the laundry for us.

The engine room was my place of work. Every time we took on supplies the engine rooms and boiler rooms received a ration of coffee, sugar and canned milk and also other smuggled goodies.

Shipfitters had fabricated two types of cookers. They were made of copper. The one for making coffee was large, similar to those used for bigger parties, except ours were heated by 165 pound steam

coils in a false bottom under the cookers. It made percolated coffee, which was dispensed from a spigot near the bottom. Coffee was available anytime day or night. The other appliance was a huge pot

also heated by 165 pounds steam. In it we made fried dough, mostly at night. Our engineering crew knew how to pilfer food. Each watch had to record the temperature in the walk-in freezer therefore they

had a key to the door. After checking temperatures, eggs and meat were brought back to the engine room. Cases of canned vegetables were always stored topside. These vegetables and meat were turned into

delicious soup. Bakers made bread every other night and would make extra dough for the engine rooms. Oil was put into the soup pot and used to make fried dough. I remember several times they made wine

using large cans of berries and bakers yeast. Even alcohol was available if you knew how. Our evaporators that were used to make fresh water had to have its tubes scaled every so often. Torpedo alcohol

was used in the procedure. With a little conservation some always remained to be mixed with pineapple juice.

Our heads (bath rooms) were always clean, but basic, lines of sinks and communal showers. The latrine consisted of a long trough with wooden slats fastened at regular intervals. Water rushed in at

one end and carried the sediment out the other. I remember one Christmas dinner we were served turkey. Luckily we were at anchor. The heads were full with sick sailors and those that couldn't find a

seat used pails or hung their bottoms over the side of the ship. During this period of time we never could have gotten under way, the whole ship was too sick.

Crossing the equator the ship had an initiation for the first timers. That morning the Shellbacks (those who had already crossed) were fed steak and eggs for breakfast, while others had cereal. Then

the initiation began. A judge decided your fate. A barber cuts designs in your hair and smears it with Copal Tight, a cream used to seal steam pipe joints. The only way to get rid of this was to have your

head shaved. Ahead of time the Shellbacks had prepared shillelaghs made of a canvas tube a couple of inches in diameter filled with cloth and soaked in water overnight. Next you were forced to kiss the

babies belly (I don't know the symbolism of the baby). A fat Boatswain Mate with a sheet for a diaper and a mercurochrome belly button sits on a low seat, and as you bend over someone with a shillelagh

lifts you off your feet with a whack on the behind. Next came the doctor, one of his specialties was an electric shock. A huge tube of canvas loaded with garbage proved too hard to crawl through so the

garbage was dumped onto the deck and you had to slide through on your belly. Next a double row of men with shillelaghs were swinging at your backside and hitting everywhere as you ran down the deck between

them. Everyone had huge welts all up their backside. During this time we were clothed in shorts only, and stunk to high heaven. This is only a few of the ordeals suffered this day. A few men refused to

participate in the whole initiation. It all sounds very childish to me now besides being dangerous, and remember we were in enemy territory.

A picture in my album reminded me that we also had pets. Someone brought a dog on board at San Francisco. He was a friendly dog of unknown ancestry. At Pearl a beautiful white Spitz appeared. She and

he stayed with us throughout the whole tour. They of course mated and had three puppies; these were adopted by other ships. They were lucky dogs not to have washed over board. When we arrived back at Pearl

the male abandoned ship, while later, stateside, the female found a home with one of the officer's families.

Back to my travels. After the raid on Tokyo we returned to Iwo Jima to pick up transports of Marines escorting them to Guam, then on to Hawaii. Entered Pearl Harbor as Roosevelt's death was announced over

the loud speaker. San Francisco and Mare Island was our next stop. After several weeks I headed home for 30 day leave. VE day was celebrated during my leave. Returned to my ship to find all my gear stolen

or scattered by Seabees who were brought aboard to stand fire watch while the crew was on leave.

Repairs were completed and we again returned to Hawaii, then on to Eniwetok, Marshall Islands. At Eniwetok we were ordered flank speed to Guam. We arrived in Guam Harbor the afternoon that Japan announced

its initial surrender, which was the day before the formal surrender was announced in the states. All the ships celebrated that night. Next morning we left with transports of Marines safely escorting them to

Japan. Then we rejoined the task force. During the signing of the surrender terms on the Missouri, we were assigned picket duty in outer Sagami Wan (outer Tokyo Harbor). Later escorted a demolition ship to

various Jap islands and into the Sea of Japan to destroy Marine installations.

I said before that I never had liberties, but when the war was over we managed to get ashore several times in Tokyo and Yokosuka. Some areas of Tokyo were really messed up by our bombers. Near the palace

nothing had been destroyed. I walked in the park outside the palace walls. A moat of water separated the park and palace walls. No one was allowed beyond the moat. Across the street from the palace was a

large hotel, which General McArthur took over for his headquarters. Beyond the palace, one could see the snow capped peak of Mt. Fuji. The first time ashore, I noticed that the Japanese would step off the

sidewalk into the gutter and bow as a service man passed. It was not long before they would push and shove like a New Yorker.

At last the hour arrived. We were headed home with the homeward bound flag streaming from the flag hoist. The trip to San Francisco was routine. Here, I made the mistake to choose traveling across country.

After three days at a staging area, I boarded a troop train to Long Island, New York. I was discharged from the Navy at Lido Beach, Long Island, where several years before I had waited for my ship before going overseas.

All rights reserved by Charles E. Werner, January 1998 with revisions January 2016

DO YOU WANT TO READ THE MEMOIRS OF ANOTHER SEAMAN OF THE BRONSON? CLICK HERE!

DISCHARGED 7 JANUARY, 1946 - RATE - ELECTRICIANS MATE 1ST CLASS

ASIATIC PACIFIC RIBBONS -----------------9 STARS

PHILIPPINE LIBERATION RIBBON---------2 STARS

AMERICAN THEATRE RIBBON

VICTORY RIBBON

GOOD CONDUCT MEDAL

THIS IS THE FINE PRINT

You are visitor #